Table of Contents

- Understanding Power in Sociology

- Authority: The Legitimation of Power

- Social Stratification: The Structure of Inequality

- The Interrelationship Between Power, Authority, and Stratification

- The Dynamics of Power, Authority, and Stratification in Modern Societies

- Conclusion

The relationship between power, authority, and social stratification represents one of the most fundamental and enduring concerns within sociology. These three interlinked concepts explain how societies are organized, how individuals and groups maintain control, and how inequality becomes embedded within the fabric of social life. Power constitutes the ability to shape outcomes and influence others; authority gives legitimacy and stability to that power; and social stratification formalizes these relations into enduring hierarchies. Together, they form the backbone of political organization, economic production, and cultural reproduction.

To fully grasp the complexities of modern society, it is essential to understand how these dimensions intersect. Power without legitimacy breeds resistance and instability; authority without real power becomes symbolic and ineffective; and stratification institutionalizes both, ensuring that hierarchies endure across generations. The following discussion unpacks these relationships, showing how they operate historically, theoretically, and practically across diverse societies.

Understanding Power in Sociology

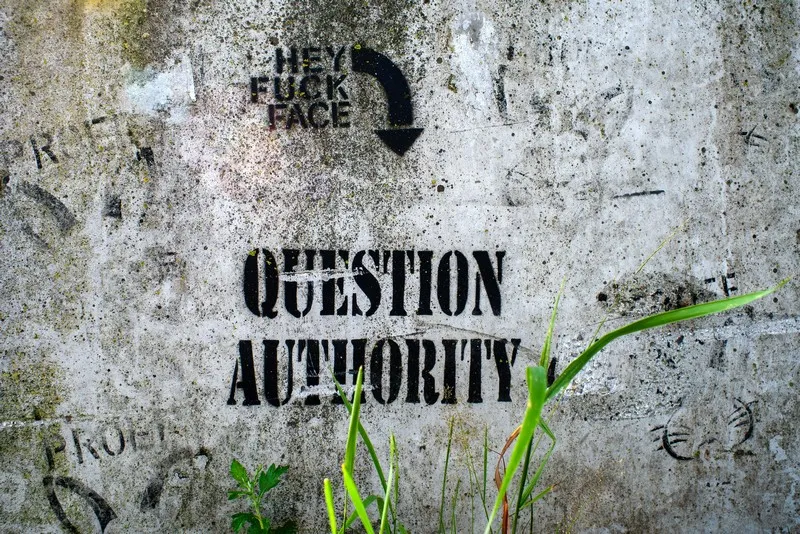

Power is one of the most central concepts in sociology because it underlies all forms of social relations. It can be exercised through coercion, persuasion, or institutional authority. Power is not confined to overt domination—it can also manifest through the subtle mechanisms that shape behavior and thought. Every society is organized around the distribution and exercise of power, which defines who gets to make decisions, who benefits from them, and who is excluded.

Dimensions of Power

Power operates along multiple dimensions, encompassing direct control, economic influence, ideological manipulation, and social legitimacy. Sociologists distinguish between its visible and invisible forms:

- Coercive power: Relies on physical force or the threat of punishment. The state, police, and military are institutions where coercive power is most visible.

- Economic power: Derives from the control of resources, production, and wealth. Those who command economic capital can shape social structures by influencing employment, consumption, and access to opportunities.

- Ideological power: Operates through control of ideas and meanings. Media, religion, and education serve as key sites for shaping collective consciousness, legitimizing inequality by presenting it as natural or deserved.

- Social or relational power: Functions within networks of influence and trust. Prestige, reputation, and charisma can generate compliance even without coercion or wealth.

Power as Structure and Process

Power is not a possession but a relation—it exists wherever individuals or groups interact. It is dynamic, situational, and constantly negotiated. Some theorists view power as diffuse and omnipresent, embedded within discourse, institutions, and everyday practices. Others see it as concentrated in the hands of elites who use it strategically to maintain privilege. Both perspectives highlight that power is both enabling and constraining: it allows coordination and governance but also produces domination and exclusion.

Power can also be productive, not merely repressive. It shapes desires, norms, and identities, influencing how people think of themselves and others. Through power, societies define what is acceptable, moral, or rational. Consequently, understanding power means examining both its visible mechanisms—laws, governments, corporations—and its invisible forms—cultural norms, gender expectations, and ideological assumptions.

Authority: The Legitimation of Power

Authority transforms power from brute force into legitimate rule. It is power accepted as rightful, binding, and socially valid. While power may rely on coercion, authority depends on consent and belief in legitimacy. Authority structures ensure that individuals comply with rules not merely out of fear, but because they regard them as just, moral, or necessary.

Types of Authority

Different forms of authority arise depending on how legitimacy is constructed:

- Traditional Authority: Founded on customs, lineage, and the sanctity of age-old practices. It thrives in patriarchal families, monarchies, and feudal systems. Obedience stems from the belief that existing hierarchies are divinely ordained or naturally proper.

- Charismatic Authority: Derives from the exceptional personal qualities of a leader. Charismatic figures—religious prophets, revolutionary leaders, or reformers—inspire devotion through their perceived vision and heroism. However, this form of authority is unstable, often dependent on the charisma of a single individual.

- Legal-Rational Authority: Rooted in established laws, procedures, and bureaucratic norms. It defines the essence of modern governance. Authority here resides not in individuals but in offices and rules. Bureaucracy ensures predictability, efficiency, and depersonalized order, even though it can also generate alienation.

The Function and Fragility of Authority

Authority provides the moral and structural foundations for governance. It allows institutions to function smoothly without relying on constant coercion. When citizens, employees, or students perceive authority as legitimate, they obey voluntarily, enabling large-scale coordination. However, legitimacy is never fixed—it must be continually renewed through performance, transparency, and fairness. When authority becomes corrupt or fails to meet social expectations, its legitimacy erodes, often leading to crises of power, rebellion, or reform.

Authority also mediates between power and stratification. By legitimizing inequality, it naturalizes hierarchy: the manager’s authority over the worker, the teacher’s over the student, or the state’s over its citizens. Authority thus maintains social order by moralizing power relations.

Social Stratification: The Structure of Inequality

Get the full article AD FREE. Join now for full access to all premium articles.

View Plans & Subscribe Already a member? Log in.