Table of Contents

- Theoretical Foundations of Gender Nominalism

- Gender Nominalism in Sociological Research

- Implications for Gender Identity and Politics

- Broader Impacts on Society

- Conclusion

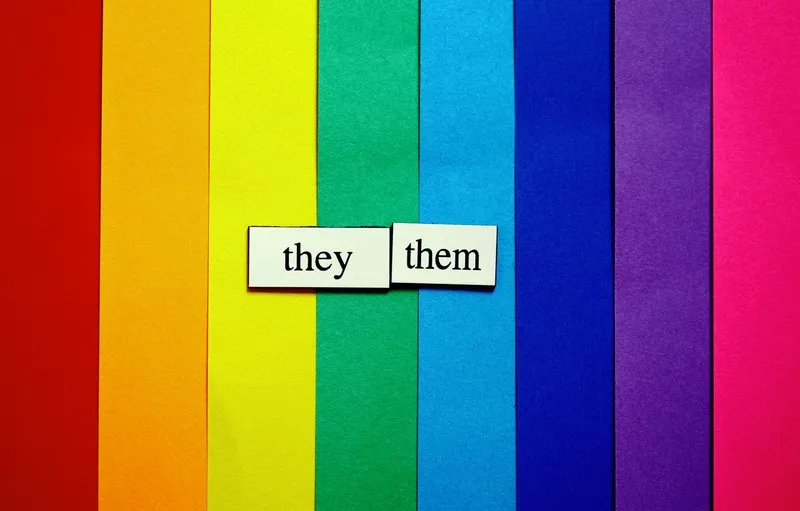

Gender nominalism, a concept rooted in the broader discourse of gender theory, offers a unique lens through which sociologists can explore the intricate and often contentious landscape of gender identity and classification. At its core, gender nominalism challenges the essentialist notion that gender categories have an inherent, fixed reality independent of social constructs and individual perceptions. This article aims to elucidate the principles of gender nominalism, trace its theoretical underpinnings, and examine its implications for sociological research and practice. Through a detailed exploration, this article will provide undergraduate students with a comprehensive understanding of gender nominalism and its relevance to contemporary sociological debates.

Theoretical Foundations of Gender Nominalism

The Rejection of Essentialism

Essentialism posits that gender categories are natural, immutable, and universally recognizable. This perspective holds that there are fundamental, biologically determined differences between males and females that dictate their roles, behaviors, and identities. Gender nominalism, however, refutes this essentialist view, arguing that gender categories are socially constructed and contingent upon cultural, historical, and individual contexts.

Constructivist Perspectives

Gender nominalism aligns closely with constructivist theories, which assert that knowledge and meaning are constructed through social processes. According to constructivism, gender is not a fixed attribute but a fluid and dynamic construct shaped by social interactions and cultural norms. Prominent scholars such as Judith Butler have significantly contributed to this perspective, emphasizing that gender is performative – a series of acts and expressions that constitute one’s gender identity over time.

Nominalism in Philosophy

The philosophical roots of gender nominalism can be traced back to nominalism, a doctrine in metaphysics that denies the existence of universal entities and maintains that only particular things exist. Applied to gender, nominalism suggests that categories such as “man” and “woman” do not have an intrinsic reality but are names assigned to a set of socially recognized characteristics. This viewpoint challenges the notion of a universal gender binary, advocating for a more nuanced understanding of gender diversity.

Gender Nominalism in Sociological Research

Methodological Implications

Adopting a gender nominalist approach has significant implications for sociological research. Traditional methodologies that rely on binary gender classifications may overlook the complexities and variations of individual gender identities. Researchers embracing gender nominalism are encouraged to employ more inclusive and flexible methods, such as qualitative interviews and ethnographic studies, to capture the diverse experiences of individuals who do not conform to binary gender norms.

Case Studies and Empirical Evidence

Several empirical studies illustrate the application of gender nominalism in sociological research. For instance, surveys and interviews with non-binary and genderqueer individuals reveal the limitations of binary gender categories and highlight the need for more inclusive and representative frameworks. These studies demonstrate that gender is a multifaceted and context-dependent construct, supporting the nominalist assertion that gender categories are socially and individually negotiated.

Critiques and Challenges

While gender nominalism offers valuable insights, it also faces critiques and challenges. Some scholars argue that nominalism may undermine efforts to address gender-based inequalities by fragmenting gender categories and complicating collective identity politics. Additionally, there is a concern that the emphasis on individual experiences might overshadow structural factors that shape gender relations and power dynamics. These critiques underscore the importance of balancing the recognition of gender diversity with the need for collective action and structural analysis.

Implications for Gender Identity and Politics

Get the full article AD FREE. Join now for full access to all premium articles.

View Plans & Subscribe Already a member? Log in.