Table of Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Major Works and Theoretical Contributions

- Key Concepts and Themes

- Influence and Legacy

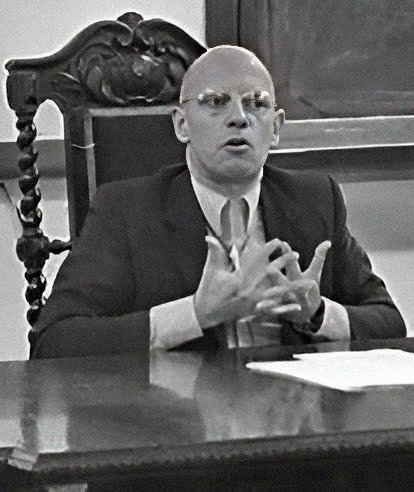

- Michel Foucault Speaks

- Conclusion

Michel Foucault was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, social theorist, and literary critic. He is best known for his critical studies of social institutions, particularly those related to psychiatry, medicine, the human sciences, and the prison system. Foucault’s work has had a profound impact on a wide range of disciplines, including sociology, cultural studies, political science, and history. His theories on power, knowledge, and discourse continue to influence contemporary thought and research. This essay provides an overview of Foucault’s life, his key theoretical contributions, and the enduring significance of his work.

Early Life and Education

Childhood and Early Influences

Michel Foucault was born on October 15, 1926, in Poitiers, France. His father, Paul Foucault, was a prominent surgeon, and his mother, Anne Malapert, came from a wealthy family. Foucault’s early years were marked by academic excellence and a strong interest in literature and history. He attended the prestigious Lycée Henri-IV in Paris, where he was influenced by the existentialist philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre and the structuralism of Claude Lévi-Strauss.

University Education and Early Academic Career

In 1946, Foucault entered the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) in Paris, a highly competitive institution that trained many of France’s leading intellectuals. At ENS, Foucault studied philosophy under the guidance of renowned scholars such as Louis Althusser and Jean Hyppolite. He also developed an interest in psychology and psychoanalysis, which would later inform his critical studies of mental illness and psychiatry. After earning his degree in philosophy, Foucault held various teaching and research positions in France, Sweden, Poland, and Germany.

Major Works and Theoretical Contributions

Madness and Civilization

One of Foucault’s earliest and most influential works is “Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason,” published in 1961. In this book, Foucault explores the historical development of the concept of madness and its treatment in Western society. He argues that the modern understanding of mental illness is not a natural or universal truth but rather a product of specific historical and cultural conditions. Foucault examines how the marginalization and institutionalization of the “mad” reflect broader social and power dynamics.

The Birth of the Clinic

In “The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception” (1963), Foucault extends his analysis to the field of medicine. He investigates the emergence of modern clinical medicine in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, focusing on the ways in which medical knowledge and practices are shaped by social, political, and economic factors. Foucault introduces the concept of the “medical gaze,” a form of surveillance and control that objectifies and disciplines the human body.

The Order of Things

“The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences” (1966) represents a significant shift in Foucault’s work towards the study of knowledge and discourse. In this book, Foucault examines the historical development of the human sciences, such as biology, economics, and linguistics. He argues that the ways in which knowledge is organized and classified are not neutral or objective but are influenced by underlying epistemic structures, or “epistemes,” that change over time. Foucault’s analysis reveals how shifts in these structures lead to the emergence of new forms of knowledge and ways of understanding the world.

Discipline and Punish

In “Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison” (1975), Foucault explores the history of punishment and the prison system from the late 18th century to the present. He argues that modern forms of punishment, such as imprisonment, represent a shift from the public spectacle of corporal punishment to more subtle and pervasive forms of social control. Foucault introduces the concept of “disciplinary power,” a form of power that operates through surveillance, normalization, and the regulation of bodies and behaviors. He also discusses the “panopticon,” a theoretical model of surveillance designed by the philosopher Jeremy Bentham, as a metaphor for modern disciplinary societies.

The History of Sexuality

Get the full article AD FREE. Join now for full access to all premium articles.

View Plans & Subscribe Already a member? Log in.