Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Conceptual Foundations: Transhumanism and Play

- Video Games as Laboratories of Human Enhancement

- Embodiment, Identity, and the Posthuman Subject in Gaming

- Political Economy and Ethical Implications

- Future Directions and Pedagogical Applications

- Conclusion

Introduction

In the early decades of the twenty‑first century, two cultural currents have accelerated side by side: the mainstreaming of digital gaming and the growing public visibility of transhumanist ideas. Video games now command an audience larger than that of film and recorded music combined. Meanwhile, transhumanism—the conviction that humanity can and should radically enhance itself through technology—has migrated from academic speculation into venture‑capital pitch decks, Silicon Valley laboratories, and parliamentary committees.

Games offer more than escapism; they invite players to inhabit programmable realities in which the body, cognition, and even mortality can be rewritten. These interactive worlds provide a lived‑in, affectively charged rehearsal for futures imagined by transhumanist thinkers—futures of brain–computer interfaces, genetic upgrades, nanotechnological self‑repair, and digital consciousness migration. Conversely, transhumanism supplies a cultural grammar that shapes the design philosophies of contemporary games, from loot‑drop economies to avatar customisation suites.

This article proceeds in five movements. First, I clarify the conceptual foundations linking transhumanism and play. Second, I demonstrate how games operationalise enhancement by affording players augmented bodies and expanded cognition. Third, I analyse in‑game subjectivities, showing how the avatar mediates new forms of embodied identity that trouble the boundaries between human and machine. Fourth, I foreground the political economy of game production, highlighting the capitalist infrastructures that monetise upgrade culture. Finally, I outline research and teaching agendas that treat video games as laboratories for the social life of transhumanism.

Conceptual Foundations: Transhumanism and Play

Transhumanism in Sociological Perspective

Transhumanism is often presented as a techno‑scientific inevitability, but from a sociological standpoint it is better conceived as a cultural movement that constructs particular futures to legitimate present power relations. Three analytical threads are worth noting:

- The Enlightenment legacy of perfectibility. Transhumanist discourse extends the modernist promise of progress, treating the body as a project to be optimised rather than a given to be accepted.

- Neoliberal subjectivation. Enhancement is framed as an individual responsibility: to refuse upgrading is to risk obsolescence in an imagined meritocratic marketplace of amplified selves.

- Technological solutionism. Social problems—ageing, disability, even mortality—are reinterpreted as engineering challenges, displacing collective political remedies with private innovation.

Foregrounding these threads allows sociologists to uncover the moral assumptions that shape which forms of life are deemed worthy of preservation or enhancement and which are neglected or pathologised.

The Cultural Logic of Video Games

Games are not mere entertainment; they are semiotic worlds in which rules, narratives, and aesthetics encode social values. Game scholars describe this as the ludic turn, recognising how gameplay structures everyday expectations of agency, reward, and risk. Crucially, games normalise programmability: the idea that reality is mutable, variables can be adjusted, and outcomes optimised. This programmable ontology resonates strongly with transhumanist imaginaries, legitimating the belief that biological limits are software bugs awaiting a patch.

Video Games as Laboratories of Human Enhancement

Video games provide a sandbox where enhancement is both mechanic and metaphor. They allow players to experience augmented perception, rapid skill acquisition, and modular bodily upgrades without the material risks of biomedical intervention. In effect, games simulate the phenomenology of upgrade culture, simultaneously legitimating its promises and exposing its pitfalls.

Mechanised Augmentation

- Skill Trees and Ability Points. Role‑playing games (RPGs) such as The Witcher 3 convert bodily improvement into legible data—strength +2, vitality +5—mirroring how transhumanist projects quantify human capacities through biometrics. The sociological significance lies in translating messy corporeal realities into spreadsheet rationalities, making enhancement appear empirically self‑evident and morally neutral.

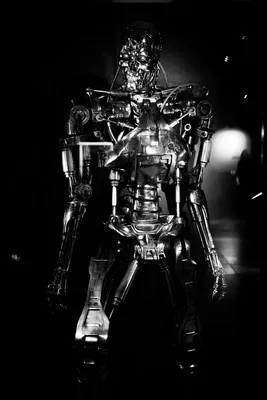

- Cybernetic Prostheses. Titles like Deus Ex: Human Revolution foreground mechanical limbs and ocular implants, inviting players to weigh the affordances of superhuman strength against the loss of “authentic” humanity. Such ludonarrative dilemmas prime audiences to consider the ethics of real‑world prosthetic innovation while simultaneously aestheticising it.

- Time Manipulation. Fast‑paced shooters employ “bullet time” mechanics that slow the external world while preserving player reflexes—a ludic shorthand for neuro‑enhancement drugs that promise hyper‑accelerated cognition. Experiencing time dilation firsthand cultivates an affective appetite for comparable abilities outside the game.

Cognitive Amplification

Beyond the avatar, games teach players to coordinate complex information streams—mini‑maps, health bars, quest logs—cultivating a distributed cognition that sociologists of science describe as an extended mind. Multiplayer environments further develop collective intelligence, as guilds analyse combat logs to optimise strategies. These practices foreshadow social formations in which algorithmic teammates, AI personal assistants, and neural implants expand the cognitive bandwidth of individuals and groups alike.

Physicality and Immersion

Virtual‑reality platforms such as Beat Saber and Half‑Life: Alyx deepen the experiential dimension of enhancement by integrating haptic feedback, spatialised audio, and full‑body tracking. Players report a heightened sense of proprioception, sometimes experiencing “phantom haptics” after removing the headset. This phenomenon parallels accounts from users of advanced prosthetics who feel touch in non‑biological limbs, suggesting that the boundaries of embodiment are learned rather than fixed.

Embodiment, Identity, and the Posthuman Subject in Gaming

The Avatar as Cyborg

Get the full article AD FREE. Join now for full access to all premium articles.

View Plans & Subscribe Already a member? Log in.