Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Origins of Petty Commodity Production

- The Social Dimensions of Petty Commodity Production

- Petty Commodity Production and Self-Employment

- The Role of Technology in Petty Commodity Production

- Contradictions of Petty Commodity Production

- Contemporary Relevance and Debates

- Influence on Social Identity and Cultural Expression

- Prospects for the Future

- Conclusion

Introduction

Petty commodity production is a term that encapsulates the production of goods or services by a small-scale producer, often working with minimal capital, tools, and labor. In many cases, these producers are self-employed individuals or small family units who rely on their own labor to create and distribute their products. At first glance, petty commodity production might appear to be only a minor player in broader economic systems. However, a deeper examination reveals that it holds significance in both historical and contemporary contexts, shedding light on the interplay between individual enterprise, market exchange, and social relations. As we explore this theme, we will unpack the origins and frameworks surrounding petty commodity production, as well as its role in shaping social relations, shaping identities, and influencing economies.

Origins of Petty Commodity Production

Petty commodity production can be traced back to pre-capitalist societies, where small producers and artisans offered goods or services, typically from their own workshops or farms, to local communities. As feudal structures began to crumble and new forms of economic organization took hold, these small-scale producers transitioned into various market-based systems. While industrial capitalism largely overshadowed many small businesses, petty commodity production did not disappear. Instead, it adapted to the shifting social and economic landscapes, acting as a persistent mode of production that occasionally mirrored—but also contested—the logic of large-scale capitalist enterprises.

Key Elements in the Historical Development

- Transition from Feudal Economies: Many small producers found new opportunities as local markets expanded and they gained autonomy over their production decisions.

- Industrial Revolution and the Rise of Factories: Artisans often faced competition from large-scale manufacturing systems, but continued to fulfill niche markets and local needs.

- Modern Context: The advent of globalization and advanced technology, ironically, both challenges and empowers small producers. On the one hand, transnational corporations can dominate markets; on the other, digital tools allow craft producers to reach global audiences.

The Social Dimensions of Petty Commodity Production

Petty commodity production is not merely an economic phenomenon. It operates within a network of social relations that shape the behavior, identity, and aspirations of small-scale producers. Social structures, cultural norms, and community ties influence the choices made by individuals who rely on petty commodity production. At times, the very act of producing commodities can reinforce existing social hierarchies, while in other instances, it can challenge them.

Ties to Community and Local Solidarity

One of the notable aspects of petty commodity production is the close link between producer and community. Small-scale producers often understand their customers on a more personal level, forging a sense of trust and community cohesion. In local contexts, these ties can encourage mutual support, collaboration, and a sense of shared identity. Moreover, community pressure and local norms often guide production processes, ensuring that quality, ethics, and relationships remain crucial.

Stratification and Inequality

While some petty commodity producers thrive, others struggle to compete against better-funded rivals. This duality can reinforce or even exacerbate existing social inequalities, particularly when certain groups lack access to capital, technology, or distribution channels. Social stratification may persist within petty commodity production, reflecting broader social inequalities based on gender, ethnicity, or class.

Petty Commodity Production and Self-Employment

One of the hallmark features of petty commodity production is self-employment. In theory, self-employment allows individuals to have greater autonomy over their labor processes, their time, and their decision-making. In practice, however, being self-employed can also mean assuming higher levels of risk and uncertainty. Moreover, this balance between autonomy and precarity is shaped by broader market forces and socio-political contexts.

Autonomy Versus Precarity

- Autonomy: Self-employed producers typically set their own schedules, choose their materials, and decide on production techniques. This can be empowering, especially when compared to wage labor under an employer.

- Precarity: Market fluctuations, limited access to credit, and lack of formal labor protections can put small producers in vulnerable positions. They often bear the brunt of economic downturns without the safety net of unemployment benefits or social security.

Household Labor and Gender Dynamics

Petty commodity production often relies on the labor of households, including spouses, children, and extended family members. This can reinforce traditional gender roles if women’s labor becomes undervalued or invisible. On the flip side, the household-based nature of this mode of production can sometimes facilitate more equitable divisions of labor, particularly where family members share responsibilities and profits.

The Role of Technology in Petty Commodity Production

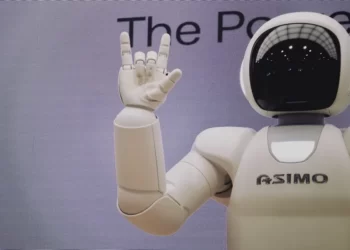

Technology has played a mixed role in shaping petty commodity production. Historically, the arrival of mechanized production posed a threat to craft producers. Nevertheless, contemporary technological developments, particularly digital platforms, offer new opportunities.

Digital Platforms and Global Reach

Small producers now have the potential to reach markets beyond their local area. Online marketplaces, social media, and e-commerce platforms can connect petty commodity producers with global customers in ways previously unimaginable. Yet, leveraging these digital tools requires a certain level of technological literacy and investment, and not all small producers have equal access.

Automation and Efficiency

On the production side, automation can reduce labor time and cost. However, adopting automation can be expensive. Moreover, for producers who rely on unique, handcrafted goods, automation might conflict with the artisanal identity of the product. Balancing the adoption of technology with the preservation of craft traditions remains a complex dynamic within petty commodity production.