Table of Contents

- The Foundations of Symbolic Interactionism

- Symbols and Meaning in the Educational Context

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- Peer Interactions and Group Dynamics

- The Hidden Curriculum

- Identity Formation in Educational Settings

- Implications for Educational Policy and Practice

- Conclusion

The field of education is often analyzed through various sociological lenses, each offering unique insights into the ways schools and learning environments shape individuals and societies. Symbolic interactionism, a micro-level sociological perspective, focuses on the everyday interactions, symbols, and meanings that influence human behavior. This approach provides valuable insights into how education functions as a social institution, emphasizing the roles of interpersonal dynamics, communication, and shared understandings. In this article, we explore the symbolic interactionist view of education, examining its core principles, key concepts, and implications for understanding the educational experience.

The Foundations of Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism is rooted in the works of George Herbert Mead and Herbert Blumer, emphasizing the role of symbols and interactions in shaping behavior and societal structures. This perspective asserts that human behavior is influenced by the meanings individuals attribute to objects, events, and interactions. These meanings are not static but are continually negotiated and interpreted through social interactions.

In education, these principles highlight how students, teachers, and administrators construct and navigate shared meanings. For instance, a grade is not merely a letter or number; it represents achievement, potential, and societal expectations, all of which are influenced by individual interpretations.

Symbols and Meaning in the Educational Context

Symbols in education are pervasive and influential. Grades, diplomas, uniforms, and classroom arrangements all carry significant meanings. Consider the following examples:

Grades and Assessments

Grades and assessments extend far beyond their function as measures of academic performance. They symbolize societal values such as meritocracy, discipline, and intelligence, reflecting broader cultural attitudes toward success and achievement. A high grade often becomes a symbol of competence and diligence, eliciting pride and reinforcing positive self-concepts in students. Conversely, a low grade can carry the symbolic weight of failure, potentially leading to feelings of inadequacy or disengagement. These dynamics are not merely personal; they are deeply embedded in social contexts. Teachers may interpret high grades as a sign of effective teaching, while parents often see them as indicators of future prospects. For students, grades can become a central part of their identity, influencing their aspirations and how they are perceived by peers.

School Traditions and Rituals

School traditions and rituals serve as powerful symbols that reinforce community, continuity, and shared purpose. Graduation ceremonies, for example, are not merely celebratory events; they mark significant transitions and symbolize achievement, perseverance, and readiness for the future. Similarly, events like sports days or annual assemblies strengthen communal bonds by creating shared experiences and emphasizing collective values. These rituals also serve to communicate the institution’s ideals—discipline, teamwork, and excellence—to students. The symbolic power of these traditions lies in their ability to embed institutional values into the consciousness of participants, shaping how they view their roles within the broader community.

Classroom Dynamics

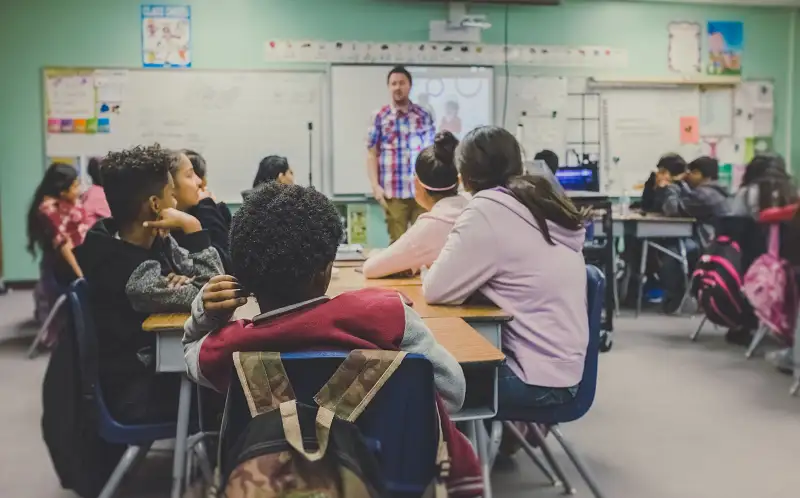

The dynamics within a classroom are a rich tapestry of symbolic interactions that shape the learning experience. Seating arrangements, for instance, are often laden with implicit messages about hierarchy and authority. A teacher’s positioning at the front of the room symbolizes control and expertise, while students seated in the back may be perceived—or perceive themselves—as less engaged. Similarly, the tone and language used by a teacher convey expectations and respect, significantly impacting students’ self-esteem and motivation. Even the use of physical space and materials, such as whiteboards or digital tools, carries symbolic meanings about modernity, accessibility, and pedagogical priorities. These subtle yet powerful symbols influence not only engagement but also the ways students perceive their relationship to the educational process.

Teacher-Student Relationships

The interactions between teachers and students are a cornerstone of symbolic interactionism in education. Teachers are not merely facilitators of knowledge but active participants in shaping the academic and personal identities of their students. Through everyday interactions, they communicate expectations, assign roles, and influence how students perceive themselves within the educational environment.

The Impact of Labeling

Labeling is a significant mechanism through which teachers influence students’ trajectories. When teachers assign labels based on perceived abilities, behaviors, or socio-cultural backgrounds, these labels carry lasting implications. For instance, a student labeled as “gifted” may experience a boost in confidence and motivation, as this label is often accompanied by higher expectations and enriched learning opportunities. On the other hand, a label such as “troubled” or “lazy” can stigmatize a student, leading to marginalization, reduced effort, and diminished self-worth.

These labels act as symbols that students internalize, becoming part of their identity. Over time, students may begin to behave in ways that align with these labels, whether positive or negative. For example, a “gifted” student may strive to meet high expectations, reinforcing the label, while a “troubled” student might disengage from learning, fulfilling the negative assumptions associated with the label.

The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

The concept of the self-fulfilling prophecy illustrates the profound impact of teacher expectations on student outcomes. When teachers hold high expectations for certain students, they are more likely to offer encouragement, provide additional support, and create opportunities for success. This positive reinforcement often leads students to perform in ways that confirm the teacher’s initial expectations, creating a cycle of achievement and recognition.

Conversely, low expectations can have the opposite effect. Teachers may unconsciously reduce their investment in students they perceive as less capable, offering fewer opportunities for engagement and growth. These students, sensing the lowered expectations, may disengage, underperform, or internalize a sense of inadequacy. The interplay between expectation and behavior highlights the critical role of symbolic interactions in shaping educational experiences.

The Symbolic Nature of Feedback

Feedback, whether verbal or non-verbal, is a powerful tool in the teacher-student relationship. Praise, constructive criticism, or even body language serves as a form of symbolic communication that conveys value, competence, and belonging. A teacher’s positive feedback can inspire students to take risks and pursue challenges, while negative or dismissive feedback can discourage participation and diminish confidence.

For example, a teacher’s enthusiastic acknowledgment of a student’s effort can reinforce the symbolic value of hard work, encouraging perseverance. Conversely, a lack of recognition may lead the student to question their abilities or disengage from the learning process. By understanding the symbolic weight of their interactions, teachers can foster environments that support growth and inclusivity.

Peer Interactions and Group Dynamics

Get the full article AD FREE. Join now for full access to all premium articles.

View Plans & Subscribe Already a member? Log in.