Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Defining Quasi-Religions

- Historical Emergence

- Sociological Context: Secularization and Beyond

- Psychological Dimensions of Quasi-Religion

- Conflict and Controversy

- Examples of Quasi-Religious Phenomena

- Functions and Implications

- The Future of Quasi-Religion

- Conclusion

Introduction

In the vast realm of human social organization, few constructs hold as profound an influence as religion. Typically, religion is characterized by sacred rites, theological narratives, and worship of a deity—or deities—that foster communal identity and moral guidance. Nevertheless, within the sociological tradition, researchers have identified a fascinating set of movements and belief systems that exhibit many of the hallmark features of religion without fully matching its formal definitions. These phenomena, often referred to as quasi-religions, straddle the boundary between the sacred and the secular, blending ritualistic practices, moral imperatives, and communal belonging with more secular or worldly agendas. In essence, quasi-religions are an illustration of society’s enduring quest to create frameworks of meaning and belonging, even in an era where conventional religious authority may wane.

This article explores the concept of quasi-religion by defining its core characteristics, surveying its historical and contemporary forms, and examining the psychological, cultural, and political functions it serves. Although these movements may differ from traditional religions in their emphases or origins, their ability to generate passionate devotion, moral orientation, and group coherence underscores their sociological significance. Furthermore, studying quasi-religions provides critical insights into the dynamic process by which societies reconcile secular trends with persistent yearnings for the sacred.

Defining Quasi-Religions

Key Attributes

From a sociological perspective, the term quasi-religion refers to belief systems, organizations, or movements that exhibit religious-like qualities without necessarily claiming the status of a formal religion. Identifying these qualities often involves looking for:

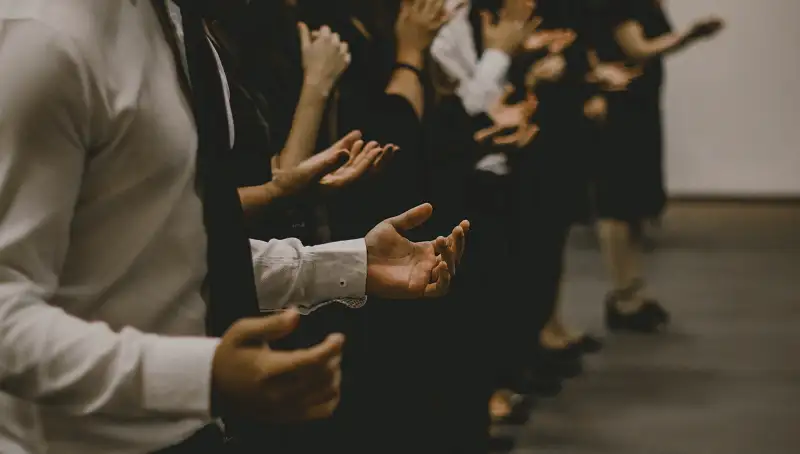

- Ritual and Ceremony: Structured behaviors or rites performed regularly, which may include initiation ceremonies, commemorative gatherings, or stylized communal events.

- Symbolic Framework: Adoption of symbols, icons, or emblems that hold deep significance and foster a sense of collective identity.

- Moral Imperatives: A set of ethical guidelines that members are expected to follow, sometimes viewed as a higher law or moral truth.

- Collective Identity: An in-group/out-group dynamic, reinforcing loyalty and group cohesion.

- Purpose and Transcendence: A worldview that provides existential meaning—explaining individual and collective purpose—even if it does not hinge on the supernatural.

While a quasi-religion may not profess a belief in a divine being or supernatural power, the structured practices, communal ethos, and sense of moral obligation often mimic those found in established religious traditions. By foregrounding these features, sociologists can delineate quasi-religious movements from purely secular institutions that focus on pragmatic or material objectives.

Distinction from Traditional Religion

There is a delicate boundary between quasi-religions and mainstream religions. Traditional religions, such as Christianity, Islam, or Hinduism, generally center on doctrines involving deities, scriptures, and long-established rituals. Quasi-religions, in contrast, can emerge more spontaneously and may focus on a single ideology, charismatic figure, or lifestyle concept without the historical lineage or explicit worship of a deity. Still, they share many sociological functions: they forge collective identities, establish moral frameworks, and create a sense of belonging among adherents.

The concept of quasi-religion thus underscores that the “religious impulse” may not always depend on belief in the supernatural but can be rooted in the human drive for purpose, moral orientation, and communal solidarity.

Historical Emergence

Early Precursors

Throughout history, when mainstream religious institutions have failed to meet the evolving needs of society, alternative groups with religious-like characteristics have emerged. Noteworthy examples can be traced back to utopian communities in 19th-century Europe and North America, where small groups attempted to create ideal societies. While they might have nominally allied with established religions, many operated independently, formulating their own rituals, moral codes, and community structures that paralleled religious life. Their purpose extended beyond pure economic or material concerns, delving into moral and spiritual domains in ways reminiscent of formal religious practices.

Mystical fraternities or secret societies, such as the Rosicrucians or certain branches of Freemasonry, also illustrate quasi-religious dynamics. Members adhered to symbolic rites, hierarchical structures, and moral obligations that evoked the sense of sacred duty and solemn commitment. Even in times when strict religious doctrines were entrenched, these groups managed to carve out a distinctive spiritual—or quasi-spiritual—space on the margins of mainstream religious life.

Modern Developments

In modern times, quasi-religions have taken on new forms, reflecting the complexity of contemporary social structures. Political ideologies that border on the dogmatic, new age movements that blend spirituality with alternative therapies, and even fervent fan communities organized around celebrities or creative works can exhibit quasi-religious traits. These developments are magnified by advanced communication technologies, which allow like-minded individuals to connect easily across vast distances.

Whether in sports fandom, in brand-centric communities, or in political cults of personality, the essential attributes remain consistent: a moral or ethical dimension, rituals or repeated practices, a distinct group identity, and a sense of mission that can feel transcendent or “larger than life.”

Sociological Context: Secularization and Beyond

The Secularization Debate

Much of the interest in quasi-religions arises from the secularization debate, a longstanding discussion among sociologists about whether modernization inevitably leads to the decline of religious influence. One viewpoint holds that as societies become more scientifically oriented and economically advanced, they move away from religious belief. However, a counterargument contends that while traditional religious institutions may lose some of their authority, religious impulses manifest in transformed ways. In this light, quasi-religions are a demonstration of religion’s resilience in modern society.

Alternative Expressions of the Sacred

By framing spiritual or moral longing in secular or partially secular terms, quasi-religions illustrate that the hunger for transcendence may be channeled into different avenues. This phenomenon reveals that certain individuals and groups remain deeply invested in shared rituals, moral rules, and community belonging, regardless of whether they invoke the divine.

Thus, rather than suggesting a uniform decline in faith, quasi-religions point to a transmutation of religious impulses—adapting old patterns of worship, devotion, and ritual for new circumstances. This underscores the adaptability of social and spiritual life, showing that as one outlet for religious expression wanes, new forms can quickly emerge to fill the gap.

Psychological Dimensions of Quasi-Religion

Community and Identity

One of the critical insights of sociology is that humans are innately social creatures who seek out group affiliations and collective identities. Quasi-religious movements provide a strong basis for this communal connection. By attending gatherings or rituals, adopting the group’s symbols, and internalizing shared moral codes, members reinforce both their personal identity and their bonds with one another.

Feeling part of a larger mission or moral project can be deeply fulfilling. Often, individuals may struggle with isolation or meaninglessness if they do not have a structured worldview. Quasi-religions supply a shared narrative, purpose, and camaraderie, acting as a bulwark against the uncertainties of modern life. Such a sense of certainty can be psychologically comforting, protecting individuals from existential anxiety.

Emotional Resonance

Quasi-religions also capitalize on emotional engagement. Much like traditional religions, they may use music, chant-like slogans, or carefully choreographed rituals to evoke collective effervescence—a concept coined by the sociologist Émile Durkheim to describe the heightened emotional energy that arises in group gatherings. This collective effervescence strengthens social bonds, making the experience feel uniquely meaningful.

In some cases, the emotional resonance may be so potent that members experience these events as spiritual, even if they are anchored in secular subjects, such as political ideologies or brand loyalty. The psychological payoff—intense belonging and emotional release—can rival that found in more explicit religious worship.

Conflict and Controversy

Get the full article AD FREE. Join now for full access to all premium articles.

View Plans & Subscribe Already a member? Log in.