Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Sociology of Knowledge in a Global Context

- Knowledge Management in the Era of Globalization

- Knowledge as a Strategic Resource

- The Social Dynamics of Knowledge Sharing

- Multinational Organizations and the Politics of Knowledge

- Knowledge Management Strategies for Multinational Organizations

- Case Study Approach: A Sociological Lens

- The Future of Knowledge Management in Global Organizations

- Conclusion

Introduction

In the 21st century, knowledge has emerged as one of the most valuable assets within organizations. As globalization intensifies, multinational organizations are increasingly tasked with managing knowledge across diverse cultural, economic, and geographical contexts. This requires not only technical systems of information management but also sociological insights into how knowledge is produced, shared, and utilized within global organizations. Unlike tangible resources such as machinery or financial capital, knowledge is an intangible and socially embedded resource that requires careful cultivation.

The sociology of knowledge provides us with a critical framework for understanding how knowledge is socially constructed, contested, and institutionalized. When applied to multinational organizations, this framework reveals the ways in which power, culture, and organizational structures shape knowledge management strategies. This article explores the management of knowledge within the context of globalization, emphasizing the sociological dynamics that underpin multinational organizations, and provides a deeper understanding of the challenges and opportunities they face.

The Sociology of Knowledge in a Global Context

The sociology of knowledge emphasizes that knowledge is not neutral but embedded in social relations, hierarchies, and cultural frameworks. When applied to multinational organizations, several key dynamics emerge:

- Cultural Relativity of Knowledge: What counts as valid knowledge in one cultural context may not be recognized as such in another. For example, Western managerial techniques may clash with collectivist or indigenous knowledge systems.

- Power and Authority: Knowledge is often tied to authority structures within organizations. Global headquarters may assert dominance by privileging knowledge from the center, while marginalizing insights from peripheral branches.

- Institutionalization: Knowledge becomes embedded in routines, practices, and systems. Global organizations must navigate the institutional differences between host countries.

- Symbolic Boundaries: Organizations often demarcate which knowledge is considered professional, scientific, or legitimate, which can marginalize alternative or local knowledge forms.

Understanding these sociological underpinnings helps explain why knowledge management in multinational organizations is not simply about technology or efficiency but also about negotiation, adaptation, and power relations.

Knowledge Management in the Era of Globalization

Globalization has profoundly transformed the context in which organizations operate. Knowledge management has shifted from being an internal organizational concern to a global process involving multiple actors, technologies, and cultural frameworks. The globalization of knowledge is not a one-way process; it involves the constant interplay between local adaptation and global integration.

Key Features of Knowledge Management under Globalization

- Transnational Flow of Information: Knowledge moves across borders through digital platforms, expatriate networks, and global supply chains, but this flow is uneven and often controlled by those with greater technological capacity.

- Technological Mediation: Digital communication, cloud-based systems, and artificial intelligence facilitate but also complicate knowledge sharing. The speed of transmission can overshadow the nuances of cultural translation.

- Cultural Diversity: Multinational organizations must balance global standards with local adaptations in order to remain effective and legitimate. A policy that works in one nation might undermine trust in another.

- Complex Organizational Structures: Matrix structures, cross-border teams, and decentralized decision-making units make the coordination of knowledge more challenging but also more innovative.

- Rapid Change: Global markets evolve quickly, demanding that knowledge systems remain agile and open to transformation.

Globalization therefore amplifies both the opportunities and challenges of managing knowledge in multinational organizations. The scope of these challenges illustrates why a sociological approach is essential.

Knowledge as a Strategic Resource

Sociologists and organizational theorists often highlight the role of knowledge as a form of capital. Like economic or social capital, knowledge can be accumulated, exchanged, and strategically deployed. In multinational organizations, knowledge management becomes an essential element of competitiveness, innovation, and resilience.

Forms of Knowledge in Multinational Organizations

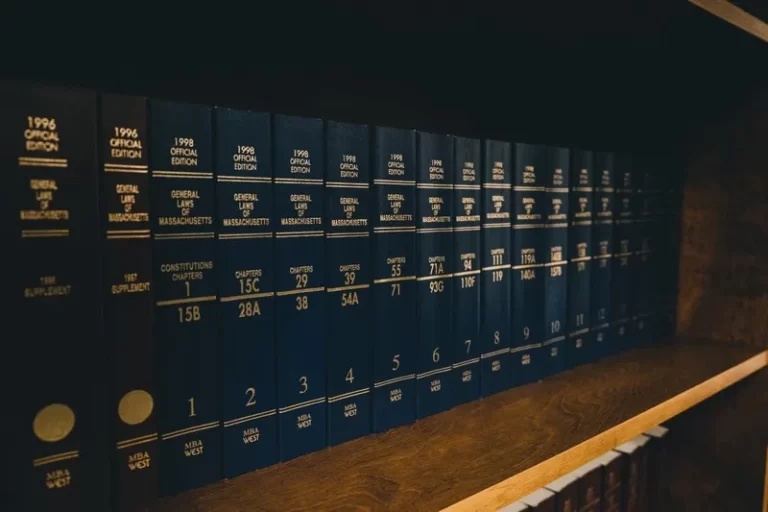

- Explicit Knowledge: Codified knowledge found in manuals, reports, patents, and databases, which is relatively easy to transfer but may lack cultural depth.

- Tacit Knowledge: Embodied knowledge, skills, and experiences that are more difficult to articulate and transfer. Tacit knowledge often flows through mentorship and informal collaboration.

- Cultural Knowledge: Understanding of local customs, values, and practices essential for multinational adaptation. Without this, organizations risk appearing insensitive or exploitative.

- Strategic Knowledge: Insights that allow organizations to anticipate market changes, competitors, and global trends, shaping long-term strategies.

- Relational Knowledge: Knowledge developed through interpersonal relationships and trust networks, which sustain collaboration across national borders.

The challenge lies in integrating these diverse forms of knowledge into a coherent strategy that enhances global competitiveness while remaining responsive to local realities.

The Social Dynamics of Knowledge Sharing

Get the full article AD FREE. Join now for full access to all premium articles.

View Plans & Subscribe Already a member? Log in.