Table of Contents

- What is Postmodernity?

- The Historical Transition: From Modernity to Postmodernity

- Postmodernism and Sociology

- Postmodernity and Culture

- Postmodernity and Globalization

- Criticisms of Postmodernity

- Conclusion: The Future of Postmodernity

What is Postmodernity?

Postmodernity refers to the cultural, social, and intellectual condition that arises in response to modernity, which dominated much of the Western world from the 18th century until the mid-20th century. Whereas modernity is associated with Enlightenment ideals such as reason, science, progress, and the belief in universal truths, postmodernity challenges these assumptions, offering instead a world of complexity, ambiguity, and skepticism.

Postmodernity emerges as societies transition from industrial capitalism to a globalized, late-capitalist structure characterized by rapid technological advancement, consumerism, and a fractured social landscape. This shift brings about new ways of thinking about culture, knowledge, identity, and power. Understanding postmodernity is essential for grasping the significant transformations that have shaped contemporary society.

Key Characteristics of Postmodernity

Several features distinguish postmodernity from modernity. These include:

- Skepticism of Meta-narratives: Postmodernity rejects grand, all-encompassing narratives such as Marxism, Christianity, and the Enlightenment that claim to explain all aspects of the human condition.

- Pluralism and Fragmentation: Rather than a unified, cohesive society, postmodernity embraces diversity, multiplicity, and the coexistence of different identities, cultures, and perspectives.

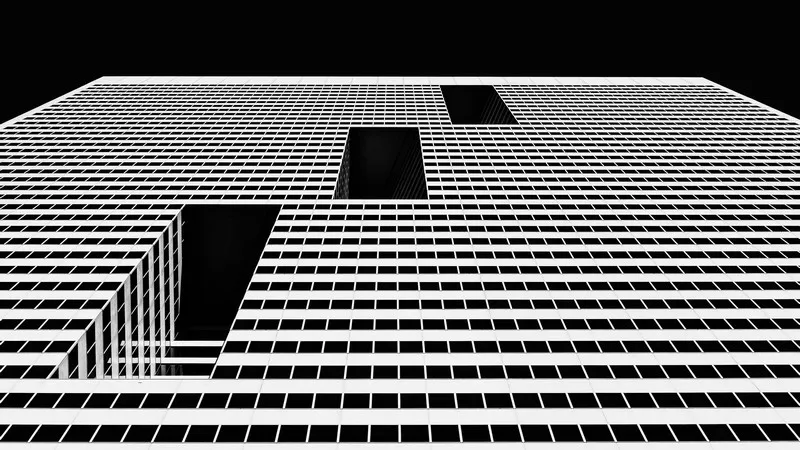

- Hyperreality: The boundary between reality and representation becomes blurred, especially in media and technology. Individuals increasingly live in a world where simulations and representations of reality are more influential than the reality itself.

- Deconstruction of Meaning: Language, symbols, and meaning are no longer seen as stable or fixed. Instead, they are subject to constant deconstruction, making interpretation fluid and subjective.

- Consumerism and Identity: In postmodern societies, identity is often constructed through consumption. People’s sense of self is less tied to social roles and more to consumer choices, brands, and lifestyles.

These elements reflect the deep shifts in both the material conditions of society and the ways in which individuals relate to the world around them.

The Historical Transition: From Modernity to Postmodernity

Modernity: A Foundation of Certainty

Modernity, which emerged in Europe during the Enlightenment, was defined by a belief in rationality, progress, and scientific advancement. Central to modernity were:

- Industrialization: The shift from agrarian economies to industrial production.

- Urbanization: The growth of cities as centers of work and social life.

- Secularization: A move away from religious authority towards a reliance on science and human reasoning.

Modernity was built on the idea that through reason and scientific inquiry, humanity could control its own destiny and improve the human condition. There was a sense of linear progress, where each generation could build on the advancements of the previous one. Social theorists like Emile Durkheim and Max Weber sought to explain the structure of modern society through frameworks of order, authority, and rationalization.

The Crisis of Modernity

However, by the mid-20th century, the foundations of modernity began to crumble. A series of global events, including the two World Wars, the Great Depression, and the collapse of European empires, led to widespread disillusionment with the idea of progress. Modernity’s promise of a better world, achieved through reason and science, seemed hollow in the face of mass destruction and global conflict.

Furthermore, rapid advances in technology and communication, along with the spread of global capitalism, began to transform the economic and social order. The rigid structures of industrial capitalism gave way to a more fluid and fragmented post-industrial society. As a result, the ideas of modernity were increasingly challenged by thinkers who sought to make sense of the new social realities.

Postmodernism and Sociology

Sociology, which had its roots in modernity, has had to adapt to the rise of postmodernity. Many sociological theories that once focused on the structural and deterministic aspects of society have shifted towards understanding the fluid, fragmented, and unpredictable nature of postmodern societies. Postmodernism in sociology rejects the idea of fixed social structures and instead focuses on how individuals construct meaning in a world that no longer provides clear or stable frameworks.

Critique of Grand Narratives

One of the central aspects of postmodern sociology is its rejection of what Jean-François Lyotard calls “grand narratives” or “meta-narratives.” Grand narratives are overarching explanations of historical events, social phenomena, or human behavior, such as Marxism’s class struggle or the Enlightenment’s faith in reason and progress.

Postmodernists argue that these grand narratives are oppressive because they try to impose a single understanding of reality on a diverse and complex world. In a postmodern society, no one narrative can adequately explain the complexity of social life. Instead, postmodernity embraces multiple, often contradictory, interpretations of events and experiences.

The Fragmentation of Social Identity

In postmodernity, social identities become increasingly fragmented and fluid. Whereas modernity provided individuals with clear roles and social identities based on factors such as class, gender, and occupation, postmodernity offers a more unstable and diverse landscape for identity formation. Key aspects of this shift include:

- The Decline of Class Identity: Traditional class structures, which were central to the analysis of modern society, have become less relevant as new forms of identity, based on culture, lifestyle, and consumption, take precedence.

- Fluid Gender and Sexual Identities: Postmodernity challenges traditional gender roles and fixed sexual identities, leading to greater recognition of a spectrum of gender expressions and sexual orientations.

- Hybrid Identities: In a globalized world, individuals often draw on multiple cultural influences to construct hybrid identities that are not bound by national, ethnic, or religious categories.

Power and Knowledge in Postmodernity

Another key area of focus for postmodern sociologists is the relationship between power and knowledge. Drawing on the work of Michel Foucault, postmodernists argue that power operates not just through force or coercion, but through the ways in which knowledge is produced and circulated. In postmodern societies, institutions such as the media, education, and even science, are seen as producing particular forms of knowledge that serve to maintain existing power structures.

Postmodernity reveals that:

- Knowledge is socially constructed, rather than objectively discovered.

- Discourse shapes reality: The language and symbols we use influence how we perceive the world, and those in power often control these discourses to maintain dominance.

Postmodernity and Culture

Get the full article AD FREE. Join now for full access to all premium articles.

View Plans & Subscribe Already a member? Log in.