Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Defining the Superstructure

- The Relationship Between Base and Superstructure

- Ideology as Part of the Superstructure

- Components of the Superstructure

- The Dynamic Nature of the Superstructure

- Conclusion

Introduction

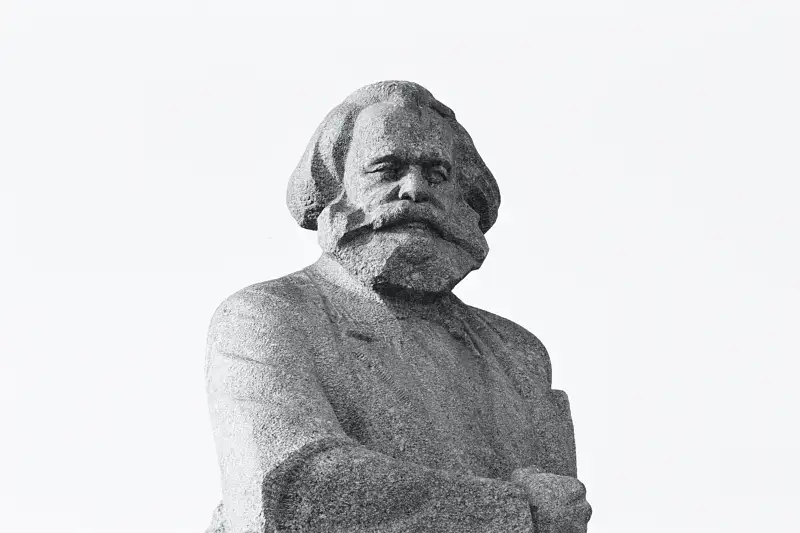

The concept of the superstructure is a fundamental component of Marxist theory, often cited but sometimes misunderstood in its nuanced relationship with the economic base. Karl Marx’s theoretical framework provides a layered analysis of society, where each stratum has its role in maintaining and reproducing the social relations of production. In Marxist terminology, society is composed of a foundational economic base and an overarching superstructure. The base refers to the economic system, encompassing the means of production, capital, labor, and the relations involved. The superstructure, on the other hand, is a collective term for all other elements of society that emerge from and serve the interests of the economic base, such as politics, culture, ideology, law, and religion.

In this article, we explore what the superstructure is, its intricate relationship with the economic base, and how it both shapes and is shaped by economic forces. This analysis will help to deepen our understanding of the dynamics between cultural, political, and ideological institutions and the economic infrastructure of society.

Defining the Superstructure

The superstructure in Marxist theory encompasses the legal, political, cultural, and ideological aspects of society. Marx and Engels presented a dualist vision of society, dividing it into two interconnected parts: the base (or substructure) and the superstructure. The base refers to the productive forces—including the means and relations of production—that constitute the economic foundation of a society. The superstructure, in contrast, includes the institutions and ideologies that arise from and serve to justify and maintain the economic base.

The superstructure serves to preserve, legitimize, and sometimes conceal the interests of the ruling class. The institutions within the superstructure—such as the government, legal systems, schools, and churches—produce and distribute ideologies that help stabilize the economic system. While the superstructure can appear to operate independently of the base, its development is deeply influenced by the economic conditions beneath it.

The Relationship Between Base and Superstructure

The relationship between the economic base and the superstructure is a dialectical one. In Marx’s vision, the base largely determines the superstructure, but the superstructure also has an influence back upon the base. This reciprocal relationship is essential to understanding how societal changes occur. Marx referred to this dynamic when he asserted that “it is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.”

To illustrate this relationship, consider the economic base as comprising the capitalist mode of production. The superstructure, which might include cultural practices, state institutions, and ideological beliefs, arises from the economic realities of capitalism. The laws that protect private property, the ideology of individualism, and even the family structures that reproduce labor power are shaped by the requirements of capitalist production. In turn, the superstructure acts to solidify the relations of production by maintaining the status quo, ensuring that the ruling class remains in control of the means of production.

Reciprocal Influence

While Marx emphasized the primacy of the economic base, the superstructure is not entirely passive. It exerts an influence back upon the economic foundation in significant ways. The superstructure can either reinforce or challenge the economic status quo. For example, a dominant ideology can provide the cultural glue that legitimizes economic inequality, thereby stabilizing the capitalist system. However, counter-hegemonic ideas can also arise from within the superstructure, challenging existing economic relations and leading to transformative social change.

One critical example of this reciprocal influence is the role of social movements. Political and ideological changes, such as civil rights movements or anti-colonial struggles, originate in the superstructure but can instigate changes in the base. Such movements often challenge prevailing property relations, labor laws, or the distribution of resources, highlighting the capacity of the superstructure to bring about transformations within the economic base.

Ideology as Part of the Superstructure

A key element of the superstructure is ideology. Ideology, according to Marx, represents the dominant ideas of a given era, which reflect and serve the interests of the ruling class. These ideas do not merely reside in individuals’ minds but are institutionalized in various facets of society, such as the educational system, the media, religion, and political discourse.

The Role of Ideology in Social Control

Ideology works to maintain social control by framing the way people think about their social environment. It tends to naturalize and legitimize the status quo, making existing social arrangements appear inevitable or even desirable. This “false consciousness,” as Marx would argue, keeps the working class unaware of their true material conditions and prevents them from recognizing their potential to effect change.

For example, in a capitalist society, ideological elements of the superstructure present the profit motive as inherently beneficial. Workers are led to believe that they benefit from the capitalist system, even when they are systematically exploited by it. By promoting ideologies such as meritocracy or entrepreneurial individualism, the superstructure obscures the inherent inequalities and contradictions of the capitalist mode of production.

Gramsci’s Concept of Hegemony

The Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci expanded on the role of ideology in the superstructure through his concept of hegemony. According to Gramsci, the ruling class maintains control not only through coercive institutions (like the police and the military) but also through a more subtle process of ideological domination—hegemony.

Hegemony refers to the ability of the ruling class to impose their worldview such that it becomes the “common sense” of society. The superstructure, therefore, is instrumental in shaping the cultural and ideological landscape, making the economic relations of the base appear as the only natural and viable option. Schools, the media, and religious institutions all contribute to this process of ideological reproduction, ensuring that the working class consents to their own subordination without the need for overt force.

Components of the Superstructure

The superstructure is composed of several interconnected institutions and cultural practices. Let us look more closely at some of these key components:

1. Political Structures and the State

The state plays a pivotal role within the superstructure. According to Marx, the state acts as the instrument of the ruling class, enforcing laws and policies that uphold existing property relations. The legal system is likewise integral, as it codifies the economic interests of the ruling class into law, often making the exploitation of labor a lawful and protected process.

The political system also functions to maintain class relations by offering the illusion of democracy and participation. Elections, political parties, and parliamentary debates create a façade of inclusiveness while masking the economic power imbalances that determine political outcomes. This keeps the working class invested in a system that, ultimately, does not serve their material interests.

2. Religion as Ideology

Religion is another key element of the superstructure that Marx famously described as the “opium of the people.” Religion, in Marx’s view, provides solace in the face of economic hardship, offering an illusory sense of meaning and reward. By encouraging believers to accept suffering in this life for the promise of an afterlife, religion functions to pacify the working class, detracting from their desire to change material conditions.

While this perspective may appear reductionist, it highlights how religious institutions can serve as mechanisms of social control, perpetuating the economic base by framing inequality as divine will rather than a human creation.

3. Education and Socialization

The education system is another crucial component of the superstructure, responsible for instilling the values and norms that support the economic base. Schools play a key role in what the French sociologist Louis Althusser termed “ideological state apparatuses”—institutions that perpetuate the ideology of the ruling class. From a young age, individuals are socialized to accept the discipline, hierarchies, and competitiveness required by capitalist production.

Education not only disseminates technical knowledge needed for the workforce but also cultivates a mindset that respects authority and adheres to social norms. This prepares the individual to become a compliant worker, integrated into the capitalist economic system.

The Dynamic Nature of the Superstructure

It is important to recognize that the superstructure is not static. It evolves in response to shifts within the economic base, but it also retains some autonomy, which means that cultural and ideological changes can preempt or catalyze changes in the economic realm. This dynamic relationship accounts for the complexity of social change in Marxist thought.

Historical materialism, the methodological approach proposed by Marx, suggests that changes in the mode of production lead to shifts in the superstructure. For example, the transition from feudalism to capitalism saw significant transformations not only in economic practices but also in legal structures, religious institutions, and cultural values. The rise of capitalism brought with it a new emphasis on individualism, secularism, and notions of liberty, all of which were embedded within the superstructure to support emerging economic relations.

Revolution and the Superstructure

According to Marx, true social change occurs when the forces of production come into conflict with the existing relations of production, leading to a revolutionary moment. The superstructure plays a key role in either delaying or facilitating such moments. When revolutionary consciousness grows, often stimulated by crises or contradictions within the base, elements of the superstructure—such as radical political organizations, counter-hegemonic ideologies, or revolutionary art—can help mobilize the masses for change.

Conversely, the ruling class uses the superstructure to forestall revolutionary change. By deploying ideological apparatuses to disseminate narratives of nationalism, racial division, or reformist optimism, the superstructure works to deflect attention from the exploitative dynamics at the economic base.

Conclusion

The concept of the superstructure in Marxist theory is essential for understanding how cultural, political, and ideological elements work together to reinforce economic relations. The superstructure is both a product of the economic base and an active player in maintaining and legitimizing the social order. It shapes individuals’ consciousness, helps reproduce class relations, and occasionally provides the tools for challenging those very relations.

Understanding the superstructure is crucial to grasping how power operates in society—how it is maintained, how it conceals itself, and how it might be overthrown. In Marxist analysis, no facet of society exists in isolation; each is intricately bound to the economic realities that underpin human relations. The superstructure is the lens through which we can better understand the complexities of ideology, culture, and institutions, all of which contribute to sustaining the economic status quo, until, as Marx envisioned, the forces of change ultimately prevail.

[/membership]

Get the full article AD FREE. Join now for full access to all premium articles.

View Plans & Subscribe Already a member? Log in.