Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Understanding the Nation as a Social Construct

- The Exclusionary Nature of National Belonging

- The Nation as a Landscape of Power

- Globalisation and the Reconfiguration of National Exclusions

- The Emotional Geographies of Exclusion

- Rethinking the Nation Beyond Exclusion

- Conclusion

Introduction

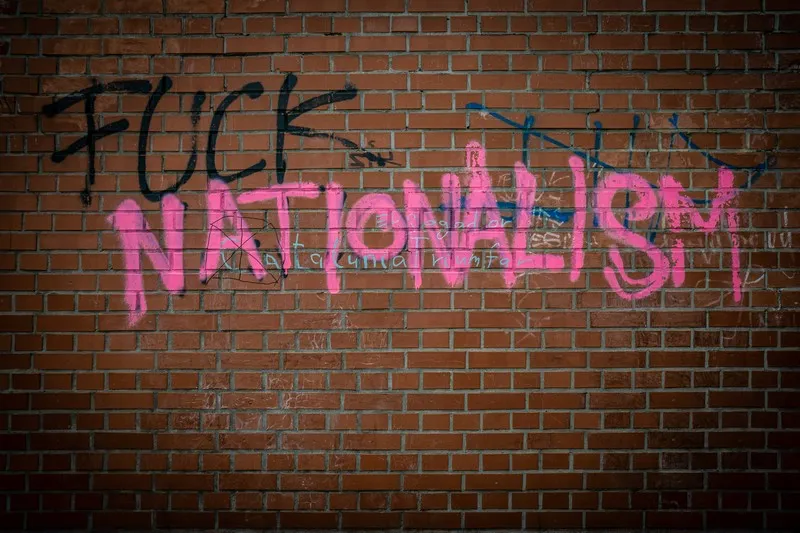

The concept of the nation is among the most powerful and enduring social constructs in modern history. Nations have provided people with a sense of belonging, identity, and purpose. Yet, the very idea of the nation is inherently exclusionary. It defines who belongs and who does not, who counts as a citizen and who is rendered foreign, and who is protected by the state versus who is treated with suspicion or hostility. Thinking about the nation as an exclusionary topography means examining how nations are mapped not only onto physical space but also onto the symbolic and social terrain of everyday life. This article explores how nations operate as landscapes of inclusion and exclusion, how boundaries are drawn and enforced, and how these processes shape contemporary societies.

Understanding the Nation as a Social Construct

The nation is not a natural fact but a socially constructed category. Its existence depends on shared stories, symbols, and rituals that bind people together in collective imagination. Nations are often imagined as timeless communities, yet they are historically recent formations, arising in tandem with industrialisation, state-building, and the spread of print culture. As Benedict Anderson argued, nations are “imagined communities” because most members of a nation will never meet, but they feel connected through shared myths of origin, common languages, and collective histories.

To conceptualise the nation as an exclusionary topography, it is essential to understand three dimensions:

- Spatial dimension: Nations are tied to specific territories, often demarcated by borders. These spatial lines not only define sovereignty but also establish who belongs inside and who remains outside.

- Symbolic dimension: Nations are organised around symbols such as flags, anthems, and monuments. These symbols reinforce unity while simultaneously excluding those who do not identify with them.

- Institutional dimension: States enforce national boundaries through citizenship laws, immigration policies, and bureaucratic practices that regulate membership.

The Exclusionary Nature of National Belonging

Borders and Territorial Exclusion

The most visible markers of exclusion within the nation are its borders. Borders function not only as geopolitical boundaries but as social filters. They regulate the flow of people, goods, and ideas, creating a distinction between insiders and outsiders. Border control systems, visa requirements, and passport regimes all embody the nation’s power to include or exclude.

This territorial exclusion often produces sharp inequalities. Migrants, refugees, and stateless persons encounter bureaucratic obstacles, surveillance, and hostility. In contrast, citizens enjoy rights, protections, and privileges that are inaccessible to outsiders. The border, therefore, becomes a site where the principle of national belonging is most intensely enforced.

Citizenship and Legal Exclusion

Citizenship is perhaps the most powerful tool of exclusion within the national framework. It transforms belonging into a legal status that grants rights to some while withholding them from others. For instance, naturalisation processes may demand years of residence, language proficiency, or proof of economic contribution. Such requirements implicitly privilege certain groups while marginalising others.

At the same time, citizenship regimes often perpetuate hierarchies within populations. Dual citizens may be distrusted, ethnic minorities may face barriers to recognition, and individuals born in the territory but without legal documents may be excluded altogether. The law becomes a mechanism that maps belonging in ways that are uneven and discriminatory.

Cultural Exclusion and National Identity

Nations also rely on cultural boundaries to delineate insiders from outsiders. Cultural exclusion often manifests through expectations around language, religion, dress, and lifestyle. Those who fail to conform to dominant cultural norms may be seen as threats to the cohesion of the nation.

For example, linguistic minorities may experience pressure to assimilate, while religious groups that diverge from the majority tradition may face suspicion or hostility. Cultural exclusion is particularly powerful because it is less visible than legal or territorial exclusion. It operates through everyday practices, assumptions, and judgments that define who is seen as authentically part of the nation.

The Nation as a Landscape of Power

Thinking of the nation as a topography allows us to see it as a landscape of power. Within this landscape, inclusion and exclusion are not merely abstract principles but tangible realities that shape how people move, live, and imagine themselves.

Hierarchies of Belonging

Nations rarely treat all citizens equally. Instead, there are hierarchies of belonging, shaped by race, ethnicity, class, gender, and sexuality. These hierarchies ensure that even within the nation, some groups are more fully recognised as legitimate members than others.

- Ethnic majorities often occupy the centre of national identity, while minorities may be framed as peripheral or problematic.

- Gender norms may dictate who represents the nation, privileging masculine images of soldiers, leaders, or workers.

- Class inequalities structure who benefits most from national welfare systems and who remains marginalised.

The national topography is therefore stratified, with layers of privilege and disadvantage mapped onto different groups.

Symbolic Violence and the Nation

Another form of exclusion operates through what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called symbolic violence. This refers to the subtle ways in which dominant groups impose their values and identities onto others. In the context of the nation, symbolic violence can manifest as the demand to “speak the national language,” to celebrate national holidays, or to honour national heroes who may not represent minority histories.

Symbolic violence enforces conformity while making alternative identities appear illegitimate. It is not enforced by physical coercion but by the normalisation of cultural dominance.

The Production of the Other

Every nation defines itself not only by who it includes but also by who it excludes. The production of the “other” is central to national identity. Migrants, foreigners, and ethnic minorities are often positioned as outsiders against which the nation defines itself.

This process of othering can take multiple forms:

- Portraying outsiders as economic threats who take jobs or strain welfare systems.

- Framing cultural minorities as incompatible with national values.

- Depicting migrants as security risks or as symbols of disorder.

Through these narratives, the nation reaffirms its boundaries and secures loyalty from insiders by highlighting what they are not.

Globalisation and the Reconfiguration of National Exclusions

Get the full article AD FREE. Join now for full access to all premium articles.

View Plans & Subscribe Already a member? Log in.