Table of Contents

- Historical Context of Marxist Thought

- Core Principles of Marxism in Sociology

- Marxism and Ideology

- Critiques and Limitations

- Marxism in Contemporary Sociology

- Practical Implications for Social Change

- Global Perspectives

- The Ongoing Relevance of Marxist Ideas

- Conclusion

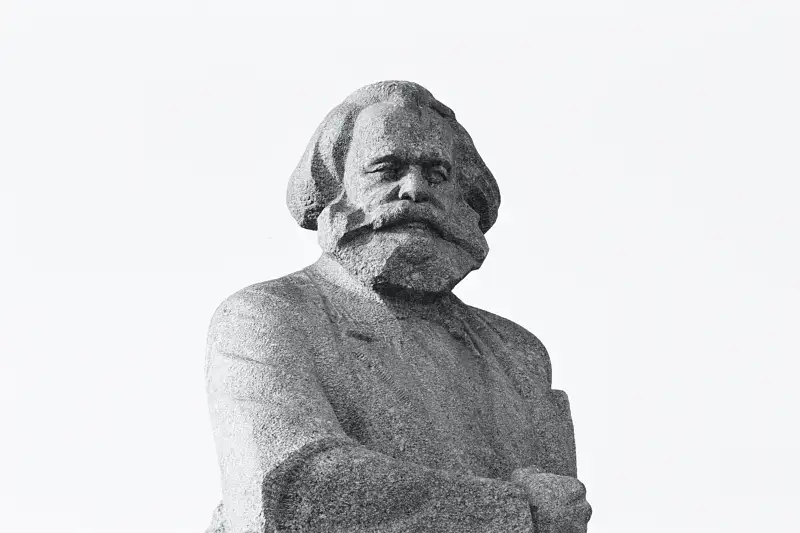

Marxism is one of the most influential theoretical perspectives in the social sciences, shaping discourse around class conflict, social structures, and economic relationships. Originating in the nineteenth century with the works of Karl Marx, it has provided rich insights into how material conditions and power dynamics influence human behavior and social organization. For many sociology students, Marxism is a cornerstone that underpins critical discussions on inequality, social change, and the distribution of power. This article unpacks the essential elements of Marxist thought, examines its key concepts, and explores its enduring relevance for sociological analysis.

Historical Context of Marxist Thought

Marxism did not emerge in a vacuum. Karl Marx, along with Friedrich Engels, developed their ideas during a period of rapid industrialization and political upheaval in Europe. Factories, fueled by technological innovations, fundamentally altered the labor process. Traditional agrarian economies were replaced by factory-based capitalism. Amid these transformations, a clear divide between the owners of the means of production (capitalists) and those who sold their labor (workers) became starkly evident.

Marxist theory, in essence, arose as a response to the social and economic ills of industrial capitalism. Marx saw a system rife with exploitation, where workers toiled in factories for long hours under harsh conditions while profits flowed disproportionately to factory owners. Against this backdrop, Marx’s ideas about class conflict, historical materialism, and the inevitable progression toward socialism and then communism took form. These ideas aimed to challenge existing power structures and present a vision of a society free from the oppression of one class by another.

Core Principles of Marxism in Sociology

Historical Materialism

One of the most crucial concepts in Marxist sociology is historical materialism, the view that material conditions—specifically, economic relationships and modes of production—form the foundation upon which social and political structures are built. According to historical materialism, the evolution of societies can be traced through shifts in how people produce and exchange goods. Marx argued that these modes of production follow a pattern:

- Primitive communal societies

- Ancient slave societies

- Feudal societies

- Capitalist societies

- (Hypothesized) Socialist and communist societies

In each of these stages, the dominant class exerts control over the means of production and, by extension, the social and political institutions that govern society. Historical materialism posits that social relations, political norms, and cultural values often serve to legitimize the economic base and perpetuate inequalities.

Class Struggle

The concept of class struggle is central to Marxism. Marx believed that history is shaped by the ongoing conflict between different social classes, primarily over control of the means of production. Under capitalism, the two key classes are:

- The Bourgeoisie (Capitalist Class): They own the factories, machinery, and other means of production.

- The Proletariat (Working Class): They do not own significant means of production and must sell their labor to survive.

Because profit in a capitalist system arises from paying workers less than the value of what they produce, Marx argued that the bourgeoisie exploits the proletariat. Workers’ labor generates surplus value—profit—for the owners, a form of unpaid labor at the heart of capitalist exploitation. This structural inequality, in Marx’s view, inevitably leads to class conflict as workers become aware of their exploitation and strive to dismantle or restructure the economic system.

Alienation

Another significant concept in Marxist sociology is alienation, a condition where individuals become detached from the products of their labor, from their fellow workers, and even from their own human potential. According to Marx, capitalist production fragments the labor process:

- Alienation from the Product: Workers often have no direct control over what they produce, lacking any personal connection with the final product.

- Alienation from the Process: The repetitive, specialized tasks in a factory setting erode creativity and autonomy.

- Alienation from Others: Workers may view each other as competitors for scarce wages or limited job opportunities, undermining community and solidarity.

- Alienation from Self: Because work becomes merely a means to survival rather than a fulfilling activity, workers lose a sense of personal identity and purpose.

Alienation thus becomes a social condition that stifles human potential and contributes to a sense of powerlessness and disenchantment within capitalist societies. By highlighting how the structure of labor leads to alienation, Marxism provides a powerful lens for understanding modern forms of job dissatisfaction, psychological distress among workers, and the social ramifications of mechanized production.

Base and Superstructure

Marx introduced the idea that society is composed of two main parts: the base (economic structure) and the superstructure (the social, legal, and political frameworks, as well as cultural and ideological forms). The base includes the means of production and the relations of production. The superstructure, in turn, arises from and is shaped by the base.

In this framework, laws, politics, religion, and cultural norms serve to reinforce and justify the economic system. For instance, a legal system that protects private property is aligned with the interests of the bourgeoisie. Simultaneously, ideological systems—such as certain moral or religious beliefs—may discourage workers from challenging the status quo by promising rewards in an afterlife or framing the social order as natural.

Marxism and Ideology

From a Marxist standpoint, ideology is not just a set of personal beliefs but a critical tool that dominant classes use to maintain their position. Ideology perpetuates the power of the ruling class by legitimizing existing social and economic arrangements, shaping public opinion, and framing reality in ways that favor the status quo.

For example, the belief in a meritocratic system—where success is supposedly determined solely by ability and effort—can obscure the structural barriers that keep certain groups from advancing. In this sense, the ideology of meritocracy may function as a veil that prevents people from recognizing how class structures and inequalities are systemically perpetuated. Thus, Marxism calls for a critical approach to ideology, urging individuals to question and unmask the underlying power dynamics.

Critiques and Limitations

Get the full article AD FREE. Join now for full access to all premium articles.

View Plans & Subscribe Already a member? Log in.